Cultivation of maize in subsistence plots (ecuaros) in the hills beyond the plain

Cultivation of maize in subsistence plots (ecuaros) in the hills beyond the plain Cultivation of maize in subsistence plots (ecuaros) in the hills beyond the plain

Cultivation of maize in subsistence plots (ecuaros) in the hills beyond the plain

The resident peons (peones acasillados) of the old hacienda did develop certain tactics of "resistance" to the disciplines that their masters sought the impose on them, by trying, for example, to cultivate their own subsistence plots instead of reporting for work in the cane fields. Landlord control in the 1920s rested on the pervasive use of surveillance and violent punishment meted out by the estate’s armed guards, the much dreaded acordada, to whom the priest, a hacienda employee, would betray workers' secrets divulged in the confessional. Nevertheless, such resistance to the terms of capitalist exploitation did not amount to a challenge to the system as such and the special historical interest of the Ciénega de Chapala lies in the fact that Guaracha was not to be destroyed by the revolutionary fervour of the workers and peasants it exploited, a majority of whom remained loyal to their patrón to the last and sympathized with the Cristero rebellion.

Bringing sown the maize harvest from the ecuaros

Land reform in the Ciénega was brought about, from above, by a "petty bourgeois" group of Jacobin revolutionaries. Their local power base lay in the clerks, traders and artisans of the provincial towns, better-off peasants in villages which had been deprived of land and economic autonomy by the expanding hacienda, and migrants returning from the United States in the wake of the Great Depression of 1929. The leader of this revolutionary faction was the son of a shop-keeper and billiard hall owner from Jiquilpan, who had married a woman from the humiliated municipal head-town of Villamar, which had lost all its lands to the Guaracha estate. After fleeing his home community and enlisting in the revolutionary army, this man was to become not merely a successful soldier and state governor, but to rise from the position of a regional caudillo to become, firstly, the principal architect of the more more radical phase of the Mexican agrarian reform in which the ejido was presented as a viable alternative to large-scale capitalist agriculture and secondly, the consolidator of the post-revolutionary political system based on the hegemony of the PRI and top-down control of peasant and labour organizations. The Ciénega de Chapala was the birthplace of Lázaro Cárdenas, and its subsequent agrarian history has, in part, been the history of a very special set of relationships between the Cárdenas family and those who benefited from the land reform that family brought to the region. Yet it is also part of a more general history, a history which is central to an evaluation of the past failings and future possibilities of land reform.

Soundclips are available, with scrolling translations, on the online version of this site, which has a slightly different design and can be found at http://nt2.ec.man.ac.uk/multimedia/

(below) Cleofas Prado, a peón who joined the struggle for land in Guaracha, describes how people stripped naked to try to sow their subsistence plots in the morning when they were expected to work in the cane without the acordada seeing them, and what happened when they were caught.

Lázaro Cárdenas attends an election party in Jiquilpan

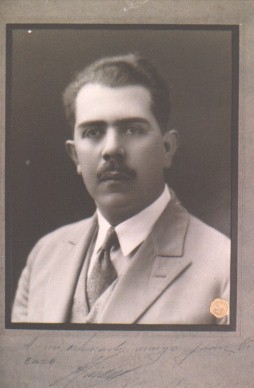

Lázaro Cárdenas as candidate for state governor

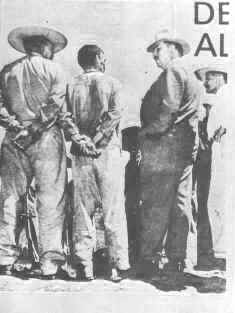

Cárdenas the Liberator, with hacienda peones