The Political Response to the Crisis

Irrigated beans sown on the same land on which the peasant holder had previously sown a small planting of beans harvested with family labour. The plot was rented by a former public sector employee, along with two others. Because of the escalating cost of irrigation water and other inputs, this venture was not a commercial success.

Irrigated beans sown on the same land on which the peasant holder had previously sown a small planting of beans harvested with family labour. The plot was rented by a former public sector employee, along with two others. Because of the escalating cost of irrigation water and other inputs, this venture was not a commercial success.

Although BANRURAL credits were still available to Ciénega ejidatarios with irrigated land until 1991, the numbers who were unable to repay their loans and were deprived of credit increased progressively, and many chose to withdraw voluntarily from the official system. Rental of ejido land increased again, rising by the end of the decade to a level similar to that of the neolatifundist era, but the pattern of rental did not replicate that of the earlier period. The renters of the Eighties did not try to manage large amounts of land, and were diverse in social origin: they included more successful U.S. migrants, former public sector professionals who had accumulated some capital in the era of statization and a range of other actors, some local, some from the bigger towns, who hoped to make a quick profit by sowing a speculative harvest or two of vegetables or beans. In some cases, the ejidatarios who had rented their land participated actively in the cultivation process, but whether or not they actually worked for the renter, the technical level of cultivation and resources invested remained closer to the standards of local peasant agriculture than to those of the larger-scale commercial producers in regional agribusiness centres like Zamora. What these new actors had in common was the cash to finance production, although they frequently failed to make the profits they expected.

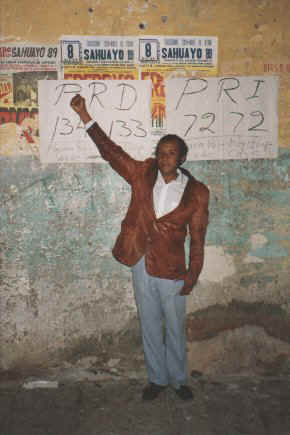

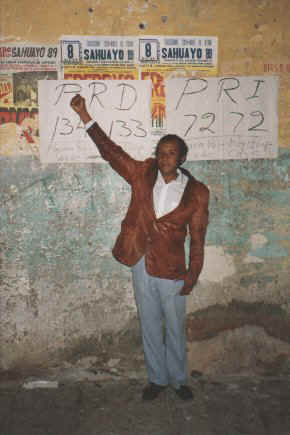

The PRD celebrates local election victory in Guaracha in 1989, although the municipio was retained by the PRI, despite protests of fraud.

The PRD celebrates local election victory in Guaracha in 1989, although the municipio was retained by the PRI, despite protests of fraud.

But there was a significant political response to the deteriorating economic situation. The ejidatarios of the Ciénega de Chapala proved fervent supporters of Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas in the electoral campaign of 1988, and most backed the newly formed PRD in the gubernatorial and municipal elections which followed in 1989, forcing the local PRI to resort to transparent frauds. These provoked occupations of town halls that were only ended by the violent intervention of the Judicial Police and army in 1990. In other parts of the state, such as the sugar growing region around Los Reyes, the PRI managed to hold on to most of its traditional rural political base in the ejidos, despite widespread dissatisfaction with neoliberal policies towards agriculture. These differences in political responses to agricultural crisis are partly explicable in terms of differing local social contexts: the PRD did actually win the 1989 municipal elections in Los Reyes (and came close in neighbouring Tocumbo), but on the basis of support from indigenous communities and landless jornaleros and urban workers, some of whom proved receptive to the mobilizing efforts of the radical independent social movement the Unión de Comuneros "Emiliano Zapata." The Ciénega communities clearly had a peculiarly intimate historical relationship with Cardenismo, although one might regard the fervour of their neocardenista sympathies as ironic, not merely because of their relatively unenthusiastic response to the original agrarian movement founded by Don Lázaro but because they had displayed little enthusiasm for his son Cuauhtémoc during his period as (PRI) state governor. Their reaction does, therefore, seem to have been against their perceived abandonment by the state and the situation produced by neoliberal policies: not only had statization brought them some tangible benefits, which were already disappearing by 1988, but the alternative represented by the capitalist transformation of the ejidos was more than a spectre in the Ciénega, with its long history of exploitation by commercial intermediaries and large-scale capitalist operations on rented ejidal land.

Those who had lived under the harsh regime of the Guaracha hacienda or had spent much of their working lives in the fields or factories of North America had good reasons to value the style of life represented by the modern ejido, even if they had resented the corruption and limited returns offered by the statized agrarian regime. Furthermore, prominent in the leadership of the neocardenista movement were ejidatarios who could be defined as a kind of "middle class."

From families which had advanced socially but were not part of the stratum of rich ejidatarios associated with neolatifundismo and caciquismo, these leaders had often been active in movements to fight corrupt officials and gain better terms for the campesinos from BANRURAL. In this sense, their perspectives corresponded to a new style of agrarian politics focused on production issues. Under Salinas, some factions within the neoliberal state itself advocated giving positive encouragement to the development of independent production orientated peasant organizations. This in part seen as a way of detaching large sections of the peasantry from independent organizations pressing demands for further land redistribution, and in part a recognition of the fact that much of the old "official" apparatus of political control associated with the official National Peasant Confederation (CNC) had ceased to be effective and that peasant resistance to the more outrageous cacicazgos which had grown out the process of statization was inevitable. But the embracing of neocardenismo by ejidatario reformers in the Ciénega reflected their (as it turned out, correct) assessment of the impact neoliberalism was likely to have on their own future prospects. Their antagonism to Salinismo was deepened not merely by further deterioration in the economic situation but by the fact that their attempts to win local political office were continuously blocked by PRI factions which used virtually any means to retain power (with apparent support from the state capital) and even alienated many of the official party’s own loyalists.

Video Clip - Click on Quicktime Logo

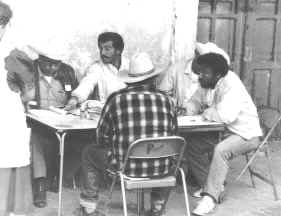

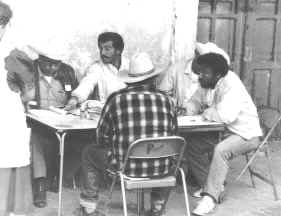

This clip shows the traditional electoral process in Guaracha, at the time of the 1982 presidential elections, when Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado was elected. This was the last time this community would vote for the ruling PRI party, as it remained loyal to Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas in the 1994 elections. In the opening sequence, we observe the role of school teachers and community and ejido officials in the electoral process. Teachers were normally expected to get out the vote for the PRI, and the refusal of many to do so in 1988 was a severe blow to the ruling party, which found threats of dismissal inadequate to staunch the tide of support for Cárdenas among these crucial local mediators of state power. Seated around the table in the first half of the clip are both the incumbent comisariado ejidal and his about to be elected successor, who subsequently became one of the principal local leaders of the PRD. In 1982, the result of the election was a foregone conclusion, with a mere twelve votes going to the opposition PAN, and none being cast for parties of the Left, but the record of the disastrous neoliberal government of De la Madrid soon made a mockery of his election slogan (seen on a poster in the clip): "For a more egalitarian society". Voting in the polling station located in the old hacienda, seen later in the clip, is presided over by the village postman, a much respected figure who was also an ejidatario. The old man with the long beard and elegant sombrero we see casting his vote was not normally resident in the village. Now in his late seventies, he had left the community more than fifty years earlier and normally resided in Chicago, returning only to vote in presidential elections. In contrast to most US migrants, he could speak fluent English, and no longer felt very comfortable about returning to his birthplace. Few residents now felt that they had strong ties of kinship or community of experience with him, and he himself associated Guaracha with the grinding poverty and endemic violence of another era. (Super-8 movie footage transferred to video, no sound.)

This clip shows the traditional electoral process in Guaracha, at the time of the 1982 presidential elections, when Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado was elected. This was the last time this community would vote for the ruling PRI party, as it remained loyal to Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas in the 1994 elections. In the opening sequence, we observe the role of school teachers and community and ejido officials in the electoral process. Teachers were normally expected to get out the vote for the PRI, and the refusal of many to do so in 1988 was a severe blow to the ruling party, which found threats of dismissal inadequate to staunch the tide of support for Cárdenas among these crucial local mediators of state power. Seated around the table in the first half of the clip are both the incumbent comisariado ejidal and his about to be elected successor, who subsequently became one of the principal local leaders of the PRD. In 1982, the result of the election was a foregone conclusion, with a mere twelve votes going to the opposition PAN, and none being cast for parties of the Left, but the record of the disastrous neoliberal government of De la Madrid soon made a mockery of his election slogan (seen on a poster in the clip): "For a more egalitarian society". Voting in the polling station located in the old hacienda, seen later in the clip, is presided over by the village postman, a much respected figure who was also an ejidatario. The old man with the long beard and elegant sombrero we see casting his vote was not normally resident in the village. Now in his late seventies, he had left the community more than fifty years earlier and normally resided in Chicago, returning only to vote in presidential elections. In contrast to most US migrants, he could speak fluent English, and no longer felt very comfortable about returning to his birthplace. Few residents now felt that they had strong ties of kinship or community of experience with him, and he himself associated Guaracha with the grinding poverty and endemic violence of another era. (Super-8 movie footage transferred to video, no sound.)

PRD supporters from Guaracha attend a rally in the neighbouring village of Jaripo

Leaders address the rally from the village bandstand

PRD occupation of the town hall in Jacona. A life was lost in the ending of the occupation in 1990.

PRD supporters inside the occupied town hall in Villamar, county seat of Guaracha, in 1989. Miguel Bautista (left), a Guaracha ejidatario and son of a hacienda overseer, acted as secretary to the party in Guaracha.

Miguel Bautista with cows stabled on his ejido parcela, 1995.

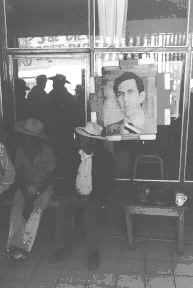

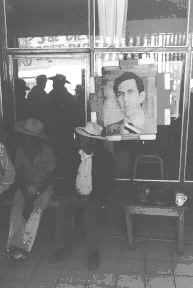

PRD defenders of the Villamar occupation guard the door in front of a portrait of Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas. Although Cárdenas ran unsuccessfully for president a second time in 1994, when the national election result was generally judged legitimate, the fortunes of his party revived subsequently. The PRD won many victories in rural municipios in Michoacán's elections in 1995, and Cárdenas was elected mayor of Mexico City in the capital's first ever direct elections, in July 1997.

Luis Prado, a PRD leader (right), headmaster of the Villamar secondary school and son of the old Cardenista agrarista, Cleofas, scrutinizes voter credentials on election day. Despite his social position and university education, Luis spent six months in the USA as an undocumented migrant in the late 1980s to assist the family finances.

Irrigated beans sown on the same land on which the peasant holder had previously sown a small planting of beans harvested with family labour. The plot was rented by a former public sector employee, along with two others. Because of the escalating cost of irrigation water and other inputs, this venture was not a commercial success.

Irrigated beans sown on the same land on which the peasant holder had previously sown a small planting of beans harvested with family labour. The plot was rented by a former public sector employee, along with two others. Because of the escalating cost of irrigation water and other inputs, this venture was not a commercial success. The PRD celebrates local election victory in Guaracha in 1989, although the municipio was retained by the PRI, despite protests of fraud.

The PRD celebrates local election victory in Guaracha in 1989, although the municipio was retained by the PRI, despite protests of fraud.