1. kinship as moral generation of community, equality and sharing morality (Fortes), amity is the axiom of kinship,but is there something special about kinship?

2. kinship as access to resources and social reproduction of livelihoods - organisational, economic (e.g. Leach in Pul Eliya)

These aspects come together in the cluster as both a moral and material unit.

THE CLUSTER: LIVING WITH PARENTS, CHILDREN AND SIBLINGS

The arrangements of houses on Parú is in a long line following the riverbank from one end of Parú to the other. All the houses are built on top of the highest available land, the floodplain levée or restinga. They are not interspersed evenly, but in clusters of closely related kin. There is no impression of a centre or focal point for any of these houses; instead all houses face the river. Thus there is no real apparent order or pattern to the houses except that they face the river, but they may be different distances from the river, (depending when they were built). What gives them order is kin relationships between them. Simply put, the cluster can be defined as a dense network of multi-family houses, which have their origin in a parental couple.

The arrangements of houses on Parú is in a long line following the riverbank from one end of Parú to the other. All the houses are built on top of the highest available land, the floodplain levée or restinga. They are not interspersed evenly, but in clusters of closely related kin. There is no impression of a centre or focal point for any of these houses; instead all houses face the river. Thus there is no real apparent order or pattern to the houses except that they face the river, but they may be different distances from the river, (depending when they were built). What gives them order is kin relationships between them. Simply put, the cluster can be defined as a dense network of multi-family houses, which have their origin in a parental couple.

The relationships in clusters, from the point of view of the head conjugal couple, are typically between themselves, their children (a sibling set), their children's spouses and their grandchildren, and their parents. These dense clusters of houses and relationships are the key to social organisation on Parú, because it is within these places that kinship and the local economies are constantly being made and the principles and values of social organisation played out.

There are two main axes upon which the cluster is internally created. The first is the parent- child relationship, which is a vertical one. The second is the sibling set, which is a horizontal axis. Both of these axes are equally important, but they have different roles in social organisation and therefore are not opposed to each other. As I showed earlier in the case of cousin relationships, the sibling one is primarily about cohesion, keeping things together, either through co-residence or affinity; whereas the vertical parent-child relationship is about continuity, in the form of developmental cycles and access to land for building houses.

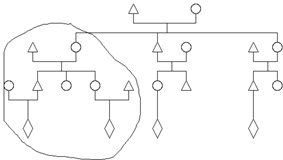

The diagram below sets out the main relationships in a cluster. In the diagram I have shown the two main types of cluster on Parú depending on its stage in the developmental cycle.

The elementary and the complex cluster on Parú

The part of the diagram inside the circle represents the idealised elementary organisation of a cluster on Parú. The whole diagram contains one possible residential arrangements of a complex cluster, which involve the parents and siblings of the head conjugal couple and their children.

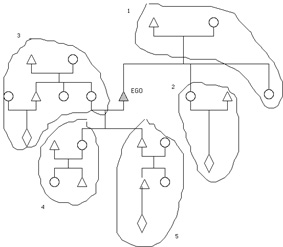

However, the above representation is an ideal one which falsely offers a fixed and two-dimensional version of what happens over time in a cluster. Thus, while the principal relationships upon which each cluster is based are structured in terms of genealogical kinship, they are always in the process of change: neither is one relationship vital nor is any one static. Furthermore, each person has a unique sphere of interaction within and across clusters that makes it difficult to draw boundaries between them. It is then perhaps more accurate to analyse the cluster on Parú with an ego-centred perspective. No one person will be involved in quite the same matrix of affinal, consanguineal and godparent relationships as another. This point is crucial to the following analysis, since there are a number of perspectives at play. No one acts in terms of his or her cluster, people act as individuals who can choose with whom they live and marry. In this way, the people who are considered a part of a cluster should be analysed from an ego-centred perspective, since there can be no objective definition of a cluster, limiting where it begins and ends.

The overlapping nature of clusters from ego's perspective

The balloons represent the different residential possibilities of inclusion into a cluster throughout an individual's life. The numbers represents the order in which they may become pertinent in ego's life.

Marriage and endogamy:

Following Overing Kaplan (1973, 1975 and 1984) we can say there are multiplicity of definitions of endogamy. The first and most obvious is marrying a cousin, particularly one considered a first cousin. Secondly, it is possible to claim that in such dense network of communal relations, as on Parú, any marriage which arises from co-residence (neighbourly proximity) in childhood can be seen to be part of what constitutes endogamy. Even if there is no clear genealogical connection or it is distant one, but the couple have nonetheless shared childhood experiences, then their marriage is a form of endogamy. It is a way of marrying geographically close. Thirdly, another type of endogamous marriage takes place when two or more siblings marry two or more siblings from another cluster. Here, the first marriage sets up relations of affinity between two clusters, and the second one replicates the first, because the second couple were already siblings-in-law. In this light and fourth, it can be said that a sororate marriage is also a form of endogamy, because a man replicates a previous marriage, this time his own, to the same sibling set. Fifth, endogamy can also be constituted by marriages of distantly linked people. This could be between people connected by marriage in the parental or grandparental generation. An example is where ego marries his FZHZD. This is a complex link and one which has no single term for Parúaros, but it is one that can give rise to co-residence and one that still brings the same sets of kin into contact. All these forms of endogamy were present on Parú during my fieldwork.

In sum, various definitions of endogamy can be made from ego's point of view, following Overing's criticism of Lévi-Strauss (Overing Kaplan 1973) and her discussion of Piaroa marriages (Overing Kaplan 1975). Endogamy can be seen from three angles. The first is marriage between cousins, people from sibling sets in the -1 or -2 or -3 generation above ego. The second is the serial and multiple repetition of affinal ties. The third is endogamy through geographical proximity. All these links characterise endogamy as settlement or residentially oriented, as opposed to other types such as kin group or alliance endogamy.

My original problem was to think about how flexibility was operating in kinship relations. Why if everything was so flexible was it not falling apart? What was there? There are a variety of strategies to maintain parental control over resources and their eventual transmission to next generation, guaranteeing survival and continued occupation. This next generation will in turn built up their own resources and build up their own cluster, and so on. In other words what appears a remarkable flexible and random social organisation has in fact incredible stability and intrinsic continuity.

Paternity and adoption: How do the idioms of blood and nature play out in the sense of kinship?

1. `adoption', which is a common way in which children move from one house to another and an important process in the development cycle. The term `adoption' in English is a thoroughly inadequate one to describe the actual relationship involved. The English term adoption carries with it too many ambiguous connotations, such as its sense of failure and marginality, to be valuable in this regard. The term filho/a de criação, `adopted' son/ daughter, and pai/mae de criação, adopted parents, are the local ones to indicate a parent/child relationship based on upbringing and procreation. It is a relatively straightforward relationship, without complications, and its frequency testifies to the lack of an elaborate distinction between relations of biology and nurture such as one observes in Western society, especially in legal terms. Adopted children are treated in exactly the same way as other children and the relationships will remain intimate over the lifetime of the people involved. The noun criação and its verb criar in Portuguese are used by Parúaros to denote a relation of creating something new, involving care and responsibility in the process. Crops are raised, criar, by their planters, as are cattle by their workers, and children are brought up, criar, by their parents. The sense is of nurture, making irrelevant the previous biological relationship or ownership. Similarly the issues of paternity and women having children by different men are down played, with the result that the biological basis is secondary to the actual relationship. This is another reason why collecting genealogies was such a difficult task during fieldwork: people would often have two fathers and mothers and there were children who recognised both sets of parents.

The following example illustrates this point about adoption and how it is related to developmental cycle. S. Ambrozio and D. Merina are the head couple of one cluster. Eight out of ten of their children had married and set up their own homes. Two were resident in another cluster and two were still living in their parents' home. Also living in the parental home were three grandchildren, the children of two daughters of S. Ambrozio and D. Merina. The eldest daughter, Lucineide, of this couple had a child with a man who refused to accept responsibility for its upkeep. So the daughter continued to live with her parents and the child was brought up by its mother and grandmother. Lucineide soon found herself pregnant again, but this time the man wanted to take responsibility. They decided to move to his parents' house. The first child of Lucineide however, though only three, did not want to leave the house, and so he stayed with his grandparents and was brought up by them. Lucineide told me that now the child calls her mamae , mum Lucineide, and his grandmother, mamae, mum. In effect, the boy has two mothers, one adopted and one biological, he recognises both in the terms of address and in behaviour. This is apparently an unambiguous situation for the people involved.

At the same time, and in the same house, there are some other relations of `bringing up'. There are two other grandchildren living in S. Ambrozio's and D. Merina's house. These are the young sons of another daughter living in the cluster, next to the parental house. I was told quite simply that the children wanted to live with their grandparents and their grandparents wanted them around to help with work in the house. These grandchildren, though, addressed their grandparents as such, avó and avó.

2. Paternity

Establishing the paternity of children is occasionally mentioned as a passing remark, but I never heard men complain about bringing up a child which he thought was not his own. Indeed, it would reflect badly on him if he did, because it might show up his inadequacy. In general, it is women who have the dominant hand in conjugal disputes. If a married woman is living with her partner's kin, at any moment she can threaten to move out and return to her parents' house, which would leave the man utterly humiliated. Men have no similar threat concerning the future of the relationship.

The sense is of nurture, making irrelevant the previous biological relationship or ownership. Similarly the issues of paternity and women having children by different men are down played, with the result that the biological basis is secondary to the actual relationship. This is another reason why collecting genealogies was such a difficult task during fieldwork: people would often have two fathers and mothers and there were children who recognised both sets of parents.

An important qualifier is legítimo, real, or puro, pure. A parente legítimo or puro is said on Parú to be a kinsperson who is related through blood, parente da sangue. Even more definitively, one woman said that the only parentes one can be sure to be parentes legÌtimos are the ones related through women. This is because, she said, one can never be sure who the father is, but the mother is always certain who her children are. It must be stressed that this does not seriously represent a matrilateral tinge to an otherwise cognatic kinship system. Nor does it indicate a male outsider quality, a kind of Ibsenesque male paranoia . It does however represent an aspect of the relative autonomy of women from men and their equality on Parú.