| Return to main page |

Malinowski himself was very much a cultural nationalist, though he tried to separate this from political nationalism. One of the problems that faced the communists when they seized power was the difficulty they had in rooting their movement in the history of Poland. Their symbols and their jargon were necessarily international and oriented towards the future. They were officially allied to the Soviet Union and official historical accounts of the Second World War years tried to put the blame for every atrocity onto the Nazis. On the other hand their opponents, both religious and secular, could mine the Polish past for powerful symbols and meanings to sustain them in their resistance. Popular memories of Soviet violence between 1939 and 1945 could not be repressed.

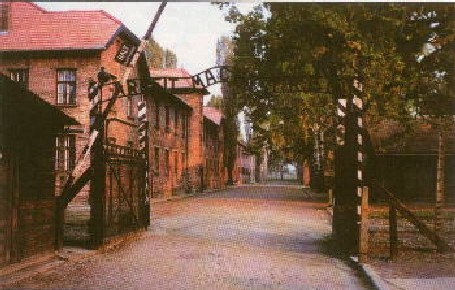

Figure 31: Auschwitz: the camp entrance

This was a very different experience from their previous trips. Prof. Dylag and Dr. Dylagowa were almost silent throughout their tour of the camps, leaving the history to be sketched by a professional guide. The enormity of the crimes committed here by Germans was really brought home to Ania by the displays of victims' hair, the pile of old shoes, and suitcases bearing Jewish names and address tags from all over Central Europe. How could Europeans do such things to other Europeans? How could Malinowski have taken it for granted that Europeans had a higher civilisation than that of Pacific headhunters?

The guide juxtaposed her account of the horrors with stories of goodness and hope. A Polish Roman Catholic priest called Maximilien Kolbe had sacrificed his own life in order to save that of another Pole. His reward was to be canonised by a Polish Pope half a century later, and to have his cell turned into a sort of shrine, a focal point of the camp tour. Ania was not sure if he had anything to do with the prominence of Christian crosses around the site. The guide was careful to state that Jews, Poles and Gypsies had all died here, but Ania wondered why Christian symbolism had to be the most prominent.

Tom was moved almost to tears when they proceeded to visit the more open spaces of the nearby camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Here you could walk under the arch through which trains had delivered the victims of Nazi genocide. The warmth of midsummer could not dispel the stench of death from this place.

Later they continued their conversation with Marek, the law student who had insisted on blaming violence in the Balkans on 'ancient tribal hatreds'. One of his grandparents had been transported for forced labour in Germany during the war. The German government had only recently agreed to pay some compensation, almost sixty years on. Marek was vehement in his denunciations of the Nazis. It was when he extended them to the Germans as a people, 'as a culture', that Tom began to feel uncomfortable. He knew from his own grandparents that many Poles had also held negative stereotypes about Jews, that they had participated in boycotts of Jewish shops in the 1930s. So wasn't it a bit too simple to attribute all the blame for Auschwitz to 'German culture'? Today's Germans could not be held responsible for the actions of the Nazis. Besides, argued Tom, the German community in Chicago was almost as large as the Polish and the Jewish, but they all got along well enough. The tragedy of Auschwitz must have more specific causes in the history of Central Europe. Perhaps it was the rapid spread of capitalism and then economic depression which led both Germans and Poles to exaggerated fears of Jews, people with whom they had lived peacefully for centuries.

Marek countered by insisting that the Jews had always wanted to maintain their distinctiveness and encouraged marriage within their group. 'That was the ultimate problem,' he insisted, 'it was a clash between cultures.'

| Return to main page |