| Return to main page |

|

|

Figure 81: Procession and open-airmass in Przemysl (photos courtesy of Stanislaw Stepien)

Ania was intrigued, but Tom would not say more about what lay in store for his family. After mass they took photos of secular ceremonies and military parades. Wlodek told Tom and Ania that the Greek Catholics had their own public procession on the occasion of the Epiphany celebrations, on 19 January. Traditionally, the Roman Catholic bishop would join our procession, which we call Jordan after the River Jordan, and our bishop would return the compliment by joining the Roman Catholic procession on Corpus Christi day. 'Of course thatís how it should be, Catholics respecting each otherís ritual calendars. But the previous Roman Catholic archbishop would never join in our procession. Even now very few of the ordinary Roman Catholic clergy encourage their people to take part in our rituals. Their identity as nationalists is stronger than their commitment to good ecumenical relations. And these attitudes donít just create poisonous political tensions in the city, they mess up peopleís personal lives as well.í

His last sentence lingered in their minds throughout lunch. Wlodek went home to his parents, Maria looked anxious throughout the holiday meal, Tom seemed nervous and impatient. When the last plates were removed the Professor delivered a short speech of thanks, which Ania found altogether pompous. When the conversation reached a natural pause, Ania thought, ëright, thatís it, itís time to get up and return to Cracow.í Then Maria quietly asked Tom to explain what they had found in the archives the previous day. He was momentarily taken aback. He looked at her father, beaming between his academic guests at the head of the table, and then at her mother and grandmother, who had already left the table in order to continue with their knitting in more comfortable chairs. Then he answered as follows:

ëOK. Our teachersí - he nodded towards the Professor and Dr. Dylagowa - ëhave encouraged us all summer to be adventurous, to apply the ideas that we learn in the context of one branch of theorising, or one part of the world, to other branches and other parts. A couple of weeks ago we heard about an anthropologist called Mary Douglas. She is faithful to Roman Catholicism as well as to the Durkheimian strand in social science. Above all, she is interested in what holds society together. One of her main contributions has been to emphasise the special attention that is given to the things that fall outside the standard classification schemes - these things are often seen as abominations and exceptionally polluting, or they may, like the pangolin in Central Africa, be ascribed a privileged mediatorís role on the basis of their peculiar characteristics. To be honest, all of that stuff floated right past me in the lecture.í The Professor allowed himself a faint smile, as Tom continued. ëBut then we came on this fieldtrip, we attended the Lemko Festival and talked to some of the villagers up there. We came here to Przemysl and, even though Iíve been visiting you regularly since I was at grade school, I heard for the first time about the conflict over the Carmelite church, and what it feels like to be a Ukrainian in this city. Hasnít anyone in anthropology thought about applying Mary Douglasís ideas to ethnic categorisations? Surely this helps us to understand the situation here. For Poles, the Greek Catholics are an anomaly! They are people who claim to be Catholics and they honour the same Pope, even though heís a Pole. Yet they hold their services in Ukrainian, they allow their priests to marry (but not their bishops!), they celebrate all the holidays that we do, only two weeks later. And so on! My theory is that the Polish population of this city still has trouble coming to terms with the fact that it now constitutes about 98% of the total population, whereas until the middle of the last century it shared the space with Ukrainians and Jews. It might not be so bad if the four hundred or so Ukrainian families were Orthodox, for then we would have a clear division. We could link the minority decisively to the east, to Russia, to all our historic enemies. But no, we canít do that, because of this peculiar historical hybrid thatís existed in this region since 1596, the Greek Catholic Church. We canít forgive them for coming so close, and spoiling our nice tidy classification of east and west down the centre of Europe.

Our teachers also told us, in the tradition of Malinowski, to try to see how the various dimensions of a society fit together - or perhaps I mean a culture, Iím still not quite sure about that one. They obviously donít all fit together harmoniously. This city needs the Ukrainians economically and allows them to the bazar, but at the same time its leaders try to minimise their presence, to banish all reminders that Ukrainians were a large presence here in the past, an integral part of the city. But the dimension on which I want to focus, and I promise it wonít take long, is the dimension of kinship. Thatís what Maria and I were investigating in the archives all day yesterday. Thatís what I want to tell you all now!í

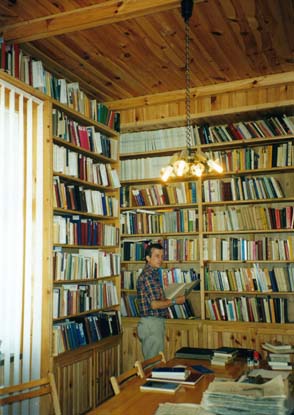

Figure 82: Tom at work in the State Archives

No one dared to interrupt this flow. Both ladies had set aside their knitting. Mariaís father filled small vodka glasses for himself and the Professor. Dr. Dylagowa declined. Maria was red and very tense.

ëI asked for the books from that particular village because I remember my grandfather telling me the name. This was the village where his father had been born and raised, before his emigration to the United States in 1912. Of course it was a Roman Catholic village. What I didnít know until now is that most of other villages in the district were Greek Catholic. And they intermarried! It looks absolutely clear that the mother of my great grandfather was, at least by birth, a Greek Catholic from Y, that is to say, a Ukrainian and not a Pole. That means, Uncle,í - he looked across at Mariaís father - ëthat the mother of your fatherís father was Ukrainian. So Maria, too, has got Ukrainian blood in her - one sixteenth, to be precise. So how in heavenís name can you be so opposed to her relationship with Wlodek, just because you categorise him as a Ukrainian?

But thatís not the end of it. Is Wlodek really a Ukrainian? This may come as a shock to you, but our research yesterday in the archive shows that Wlodek is related to all of us. He is our cousin, though relatively far removed. One of his great great grandmothers was almost certainly a sister of the great great grandfather that Maria and I have in common; but of course that lady moved from X to Y, a Ukrainian village. Later the family moved to this city, and the memory of that generation, before the First World War, when intermarriage was thoroughly routine, has died out.í

Figure 83: Tomís Diagram

Before Tomís Uncle could say anything, his mother spoke up from the corner. ëNo, no, itís not died out,í she said. ëI wanted to explain all this to you years ago, but my son refused. Now itís time to bring everything out into the open. I was born in 1924, the same year as my late husband. I can remember how the Greek Catholics celebrated their Jordan rituals on the frozen river before Hitlerís war. I donít remember it as an observer from a distance, but as a young girl in the crowd. For I was from a Greek Catholic family, and I didnít become a Roman Catholic until 1947, and then only because it was the only way to avoid deportation. Most of my own family had already been taken off to the Ukraine in 1945. I was already engaged, thatís why I stayed. My husband made me promise that I would become Polish, that we would bring up our children as good Roman Catholic Poles. And I kept this promise. I never had any more contact with my family, though I thought about them often. I kept my promise because I was afraid that it would do no good to open up all those awful events from our past.í

The old lady paused, but there were no tears. Ania thought she looked angry with her son. She continued, ëYour father was so angry when you told him that you wanted to marry your school sweetheart, the pretty girl from K. You thought he was being unreasonable, but he did have his reasons. Did he ever talk to you about them?í

Tomís uncle jabbed his vodka glass sharply onto the table and addressed his mother. ëNo, he didnít tell me anything, he didnít have to tell me. Do you really think I didnít know that you were Ukrainian? Whenever I quarrelled with anyone as a schoolkid, or disagreed with one of the bosses at the factory, your background was the very first thing they flung in my face! And do you really think I donít know about what happened in K, where the entire village converted from Greek Catholic to Roman Catholic, because it was the only way they could carry on living in their homes? Itís true, I didnít know this at first, when we met at school. You donít consider the group labels when youíre in love with an individual, a person, and her parents didnít know how to tell me when I was first taken home to meet them. I only put two and two together when I heard some older people talking in Ukrainian on the bus back to the city.í

By now his wifeís face was full of tears. She was unable to utter a word. Maria was stunned. She turned on her father: ëSo you went ahead and married the Ukrainian you loved, but just like Grandma, you would both pretend to be one hundred percent Polish! And when I happen to do just what you did, and fall in love with someone at school, you behave just as your father did and tell me to end the relationship. But times have changed, dad. We can talk about these things nowadays, thereís no need to go on seeing every Ukrainian as a source of danger, as a threat to our Polish society.í

ëTimes may have changed,í her father agreed, ëbut I wouldnít say for the better. You know whatís been happening here since the communist lid was removed. Look at all the passionate hatred that some people here direct to the Ukrainians. Iíve never gone along with any of that, as you know, but I just donít want my family to be caught up with it. Thatís the only reason why Iíve never talked to you about all this, because I donít want you to become a victim of the tensions here. We are all the same before God, Roman Catholic or Greek Catholic, it doesnít matter, but why should we expose those we love most to unnecessary dangers?í

His wife choked agreement. ëDo you know how difficult itís been for me over the years? Most of my relatives in the village are talking about going back to the Greek Catholics, on the grounds that itís their traditional church, which they only left because of the dreadful political circumstances of the 1940s. I knew you would find out about all this sooner or later.í

Ania coughed as politely as she could: ëWouldnít it be possible to join the Greek Catholic Church and continue to see yourselves as Poles in a general cultural sense? I mean, youíd carry on living here and using the Polish language in everyday life.í Dr. Dylagowa nodded approvingly as the question was put.

ëThatís out of the question,í said Mariaís father as he poured some more vodka. ëA decision to join the Greek Catholics is a public declaration that you feel yourself to be Ukrainian rather than Polish. Thatís the way it is here.í

ëIt may be like that now,í said the Professor, but I donít think it was like that a hundred years ago, when these villages were part of multiethnic East Galicia. I think in those days there were plenty of villages where Greek Catholics spoke Polish, and even some where Roman Catholics spoke Ukrainian. It was nationalist pressure, both Polish and Ukrainian, which eventually succeeded in bringing religion and national orientation perfectly into line.í

Dr. Dylagowa chimed in at this point. ëYes, and sorry Tom, but thatís why itís pointless to talk about people having ëone sixteenth Ukrainian bloodí as you said of Maria a few minutes ago. From what we have just been told, you might wish to revise this estimate. Indeed, if we copy out her family tree she seems to be more Ukrainian than Polish. But what do these labels mean? Itís perfectly possible that the families of these ladies here, who we are now reclassifying as Ukrainian, had inmarrying Poles in their earlier genealogies. I really think we should leave the business of determining identity by blood composition to that rather unpleasant phase in the history of anthropology when the discipline was put to serve the criminal objectives of the Nazis.í

The discussion continued for some time. There was general agreement on how majority-minority relations in Przemysl might be improved in the future. The Professor wanted to discuss whether any lessons could be learned for other parts of the country, or even for other parts of the world, wherever people asserted ëcultural differencesí as their basis for negative stereotypes and violence. Eventually the ladies made some more tea and resumed their knitting. Maria looked at her father and said, ëIím off to meet Wlodek now.í

ëOf course,í he replied.

Dr. Dylagowa looked at her watch: ëIím afraid we need much more research to shed light on all these matters and we canít possibly solve them all today. Our students have to take the train back to Cracow this evening. Thank you so much for your marvellous hospitality!í

| Return to main page |